(7975.93.73) Assuaging fears about mathematical diagrams

#proof-theory #philosophy-of-math #cognition

Can mathematical diagrams play an essential justificatory role in

mathematical proof? In a recent paper[1], Silvia De Toffoli suggests

the affirmative, diverging from a commonly held view that diagrams play

at most a heuristic or illustrative role in mathematical

justification[2]. She provides two important examples to demonstrate

that mathematical diagrams, subject to certain constraints, form genuine

notational systems: fundamental polygons in topology and commutative

diagrams in algebra. The basic argument is that, in either case, it is

possible to equip these diagrams with a syntax capable of supporting

logical inferences unambiguously corresponding to mathematical objects.

Furthermore, they satisfy desirable qualities of notation such as

reproducibility, stability, accessibility, and so on.

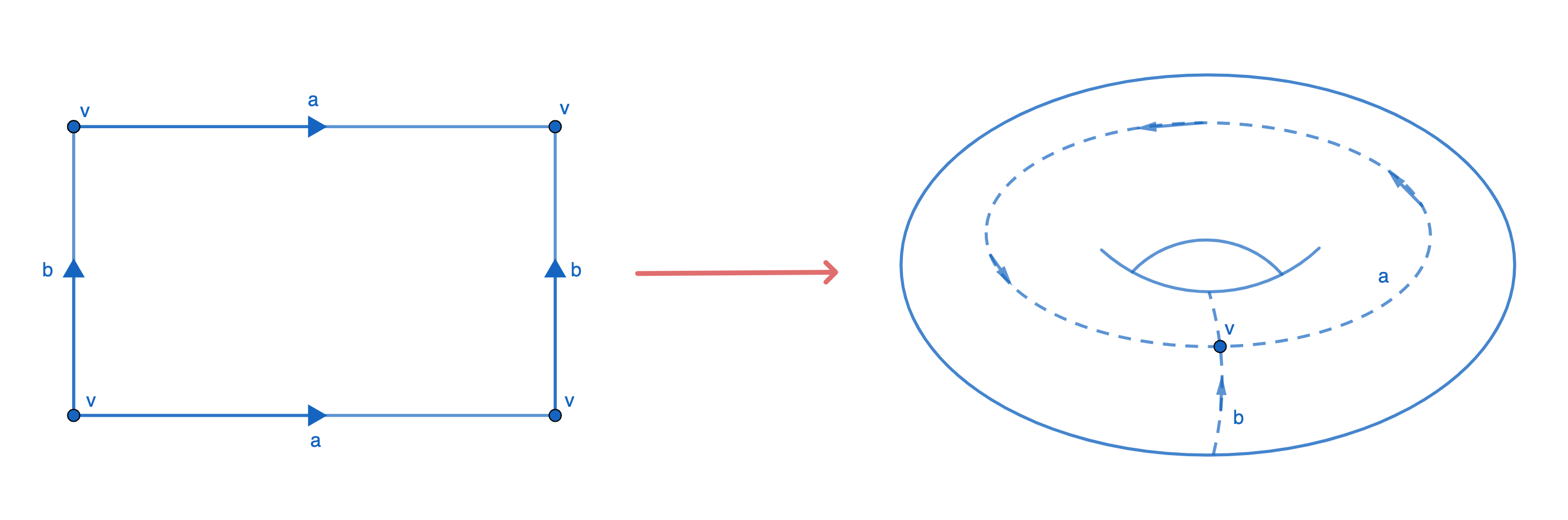

For example, consider the polygon diagram in Figure 1. The

constitutive features of this diagram -- labeled edges and vertices --

are Furthermore, it is straightforward (and, indeed, common practice)

for mathematical practitioners to reproduce these diagrams up to

non-constitutive features[3]. Finally, practitioners can not only

perform (physical or mental) manipulations to these diagrams, but,

crucially, these manipulations correspond to well-defined mathematical

operations. In this case, together matching edges of a polygon

corresponds to forming a quotient space, and a polygon corresponds to a

homeomorphism of the surface. Therefore, polygon diagrams form a

notation system for topological surfaces that is not only intuitive[4]

and natural for the topological setting, but also that supports

inferences with precise mathematical meaning.

Figure 1. A polygon diagram and the corresponding torus

Examples like this settle the issue of whether diagrams can be used

for mathematical justification, in so far as they meet agreed upon

standards of rigor and criteria for acceptability[5]; the natural

question, however, is whether there is actually epistemic merit to their

use in proofs, beyond the heuristic or illustrative value they might

provide. De Toffoli's second thesis addresses this explicitly: she

asserts the existence of a De Toffoli's justification for this claim

hinges on the nonexistence of a useful context-independent criterion for

proof identity. If one wishes to claim that two proofs of the same

proposition are he must specify a particular context of investigation.

Some examples of contexts are rigor -- two proofs of a proposition are

the same if they are equally rigorous -- and purity -- two proofs of a

proposition are the same if they use the same central idea.

The context of investigation relevant to De Toffoli's argument is that

of epistemic benefits and drawbacks, particularly as they relate to

cognitive efficiency and the practitioner's ability to grasp the overall

structure of a proof. In this setting, the primary differentiators

between proofs of the same proposition are factors contributing to

cognitive efficiency for a practitioner recreating or comprehending the

proof. De Toffoli's example of a proof involving diagrams lessening the

cognitive load on the practitioner is the snake lemma. This

fundamental result in homological algebra is somewhat tedious to prove

in prose alone, requiring the reader to bear in mind the properties of

several maps and the relationships between several abstract vector

spaces. Because of this, the result is almost always introduced, taught,

and remembered in terms of a commutative diagram -- indeed, the name

refers to the suggestive shape of the corresponding commutative diagram.

With the help of the diagram, the practitioner can both check each step

of the proof more reliably, as well as more easily grasp the global

structure of the problem. In this sense, the diagram bears much of the

cognitive burden that the practitioner carries when using the proof to

convince himself of the existence of a formal proof of the result.

The crux of De Toffoli's argument is that, in the context of epistemic

benefit, the discrepancy in cognitive efficiency of proofs of the

snake lemma with and without diagrams renders them different proofs of

the same proposition, even when they might be the same proof in the

contexts of rigor or purity. Therefore, the commutative diagram is an

essential feature of that proof in this context of investigation, and,

as such, the diagram cannot be faithfully into prose while retaining the

same proof. But how should qualities like explanatory power,

mathematical beauty, and purity fit affect the individuation of proofs

in the context of epistemic benefits, particularly in cases not

involving diagrams? This question casts doubt on whether this is even a

plausible conception of proof in the first place, or if this way of

individuating proofs might lead to undesirable results. This paper

serves as an introduction to the that De Toffoli mentions is necessary

to understand this phenomenon. In particular, I argue for a refined

understanding of proof individuation that retains the focus on epistemic

benefits and drawbacks as the primary individuator of proof

presentations, while balancing this with mathematical rigor and

mitigating undesirable judgments from subjective, agent-dependent

criteria.

In the following section, I will discuss whether epistemic benefit

actually yields a plausible, well-behaved identity criterion for proofs.

I will answer in the affirmative, with some key caveats. I will also

give a definition of an epistemic benefit, as well as a description of

the generic practitioner that might enjoy such benefits. There will be a

discussion of the commitments of engaging in this type of individuation,

with respect to mathematical rigor and acceptability. The final section

is a discussion of mathematical aesthetics and purity, which will

clarify the interplay between epistemic benefits/drawbacks and aesthetic

qualities often attributed to mathematical proofs.

Individuating Proofs

The set of all proof presentations surjects onto the set of provable

true propositions

presentations by identifying any two presentations that are mapped by

this surjection to the same proposition. However, further refinement of

this partition requires a choice of a context of investigation; as De

Toffoli discusses, there is not a satisfactory context-independent

criterion for proof identity.[6] However, there is concern as to

whether epistemic benefit is even a sensible condition for proof

identity in the first place as it relates to desirable features of

individuation, such as appropriate levels of specification,

subjectivity, universality, and so on.

But it is not immediately clear that the context of epistemic benefit is

well-behaved as a means to individuate proofs. For one -- when, if ever,

does this criterion actually equate proof presentations? In what sense

can actually be measured and/or effectively compared across proof

presentations? Furthermore, does this metric behave well with respect to

comparison across media types? That is, it is not clear a priori

whether it is even a coherent practice to compare diagrammatic and

non-diagrammatic proofs with respect to cognitive efficiency, in

general. Unless one can produce an example of a proof involving diagrams

and a proof not involving diagrams that are similar in terms of

epistemic benefits and drawbacks, the thesis that this proof criterion

renders diagrams essential to certain proofs is not reasonable.

The purpose of this section is to remedy some of these objections, as

well as to shed light on the motivation and meaning of some of the

underlying concepts. To begin with, we address the notion of cognitive

efficiency, as it relates to the epistemic benefits and drawbacks of a

proof. A boon for cognitive efficiency proffered by De Toffoli is if one

need not hold in mind a in order to see why steps are valid[7]. This

benefit is clearly seen, for example, in the case of the snake lemma; as

many of the relevant maps and their relationships are semantically

embedded in a commutative diagram, the reader is free to grasp the

overall structure of the proof, while still being able to quickly refer

to the diagram to verify inferences. In this sense, the diagram

shoulders much of the cognitive burden of understanding a proof of the

snake lemma, therefore distinguishing it from a diagram-free version of

the proof, in which the diagrammatic moves have been faithfully encoded

in prose.

Importantly, mathematical diagrams whose roles are solely heuristic or

illustrative do not contribute to cognitive efficiency in the same

sense. According to De Toffoli's description, diagrams constitute

mathematical notation when they meet the following three criteria:

a notation should be cognitively accessible: its constitutive

formal features should be clearly identified, persistent, and

stable;a notation should be reproducible: it should be possible for an

average practitioner to copy its constitutive formal features with

relative ease and reliability, possibly with the aid of different

tools such as a straightedge and/or a computer;a notation should support calculations and/or inferences: it

should be possible for an average practitioner to perform

reasonably simple manipulations corresponding to mathematical

operations.

For a given proposition

using diagrams that constitute mathematical notation and a proof

presentation

notation,

epistemic benefits. To see this, we can evaluate the criteria in turn.

To begin with, suppose

accessible. This clearly works against cognitive efficiency --

unraveling ambiguous, unstable diagrams imposes a highly nontrivial

cognitive load. Secondly, if the diagrams in

reliably reproduced by a reader, then making manipulations or changes to

the diagrams corresponding to logical inferences can only be done in the

mind of the practitioner -- again, this arrests significant mental power

that would otherwise be left to grasping the large-scale structure of

the proof and making high level inferences. Finally, if the diagrams in

certainly provide no epistemic benefit with respect to justification.

None of these epistemic drawbacks, however, are imposed by

diagrams-as-notation. Thus, the secondary refinement of proof

presentations induced by epistemic benefit is fine enough to distinguish

between proofs like

Subjectivity and agent-dependence

One might object that individuating proofs according to epistemic

benefit is not reasonable, due to possible discrepancies between

practitioners. I agree that it is necessary to mind possibly confounding

effects of being overly specific with respect to the cognitive strengths

and weaknesses of any one practitioner. However, it is still useful and

productive to make these judgments with an agent in mind; we need simply

to be careful about the precise role and nature of this agent. In order

to frame this issue more concretely, consider the following theorem.[8]

Theorem 1. Whenever a rectangle is tiled by rectangles each of

which has at least one integer side, then the tiled rectangle has at

least one integer side.

This theorem[9] was presented, along with a proof using a complex

double integral, at the 1985 Summer Meeting of the MAA, as a call to

attendees to find more simple or natural proofs of the theorem. This

call was successful: in the months that followed, several alternative

proofs of this theorem were presented, varying widely in simplicity,

techniques used, and strength (that is, the amount of generality in

which the proof may be applied). Two of these proofs are clear leaders

in terms of cognitive efficiency, though they employ strikingly distinct

techniques. Let

these two proofs.

-

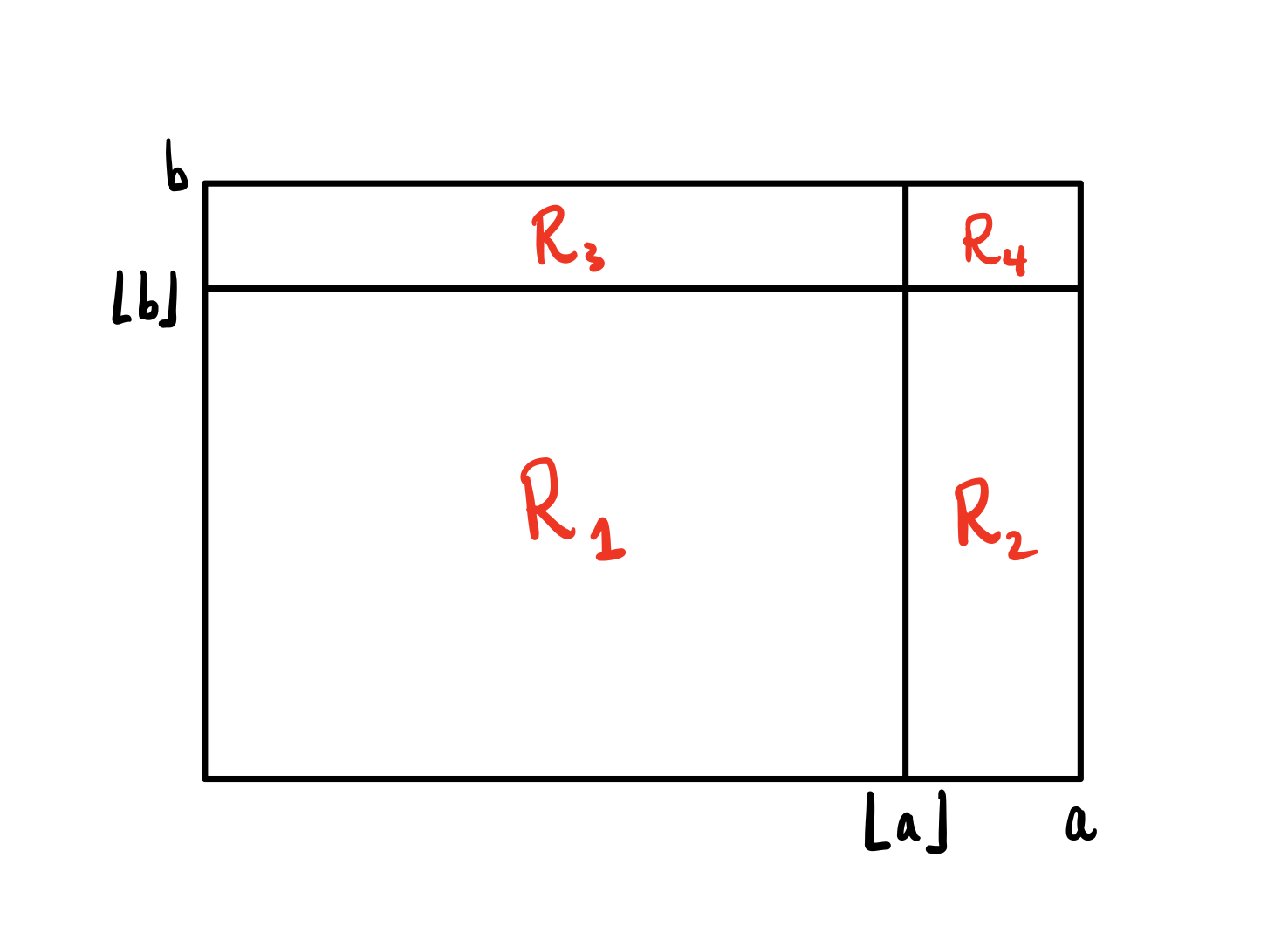

Checkerboard. (R. Rochberg) Let

be an rectangle

with a tiling by rectangles with at least one integer side, where

and are real numbers. We may assume that is embedded in

the plane with its lower-left corner at the origin. Then, consider

the lattice obtained by tiling the plane by

black and white tiles, arranged in

checkerboard fashion. Then, each of the tiles incontains an

equal amount of black and white. Thereforecontains an equal

amount of black and white, as well.Now suppose for contradiction that neither

nor is an

integer. Then we may tilewith four non-empty rectangles:

,

,

,

, as in Figure 2. Since each of , and

have at least one integer side, they all contain equal amounts of

black and white. However,does not contain equal amounts of

black and white; this can be seen by an easy check using the facts

that the sides ofare all less than and that its lower

left corner lies on a lattice point. Thus, the union

does not contain an equal

amount of black and white. This is a contradiction, so we may

conclude that at least one ofor is integral, as desired.

Figure 2. Subdividing the rectangle R for Rochberg’s checkerboard proof. -

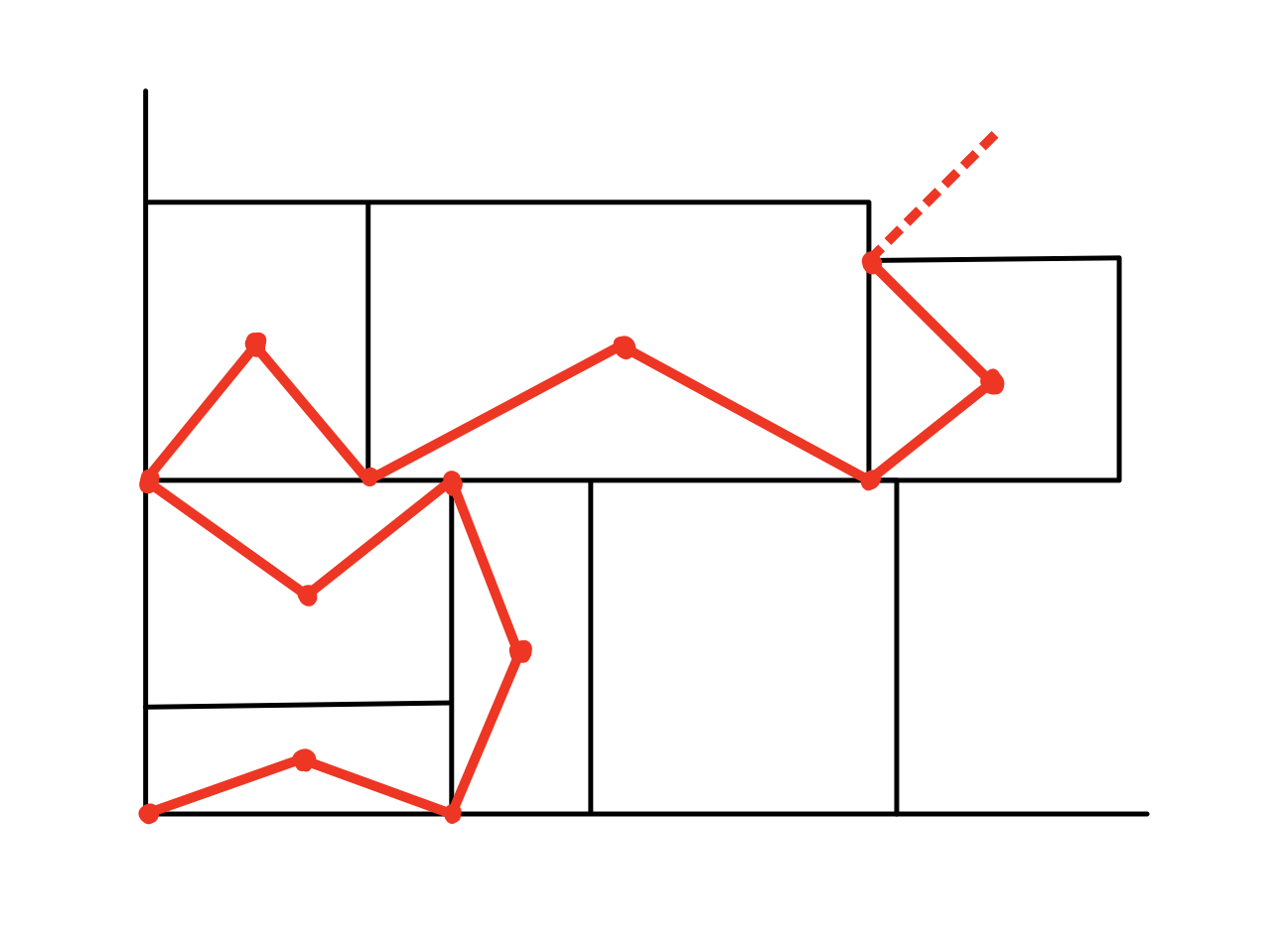

Bipartite graph. (M. Paterson) Again embed

in the plane with

its lower left corner at the origin. Letbe the vertex set of

corners of tiles with both coordinates integral, and letbe the

set of tiles. We may form a bipartite graphon the union

by connecting with an edge each point in with the

elements inof which it is a corner, as in Figure 3.

By the hypothesis, each element inhas exactly , , or

corners in. Therefore, has an even number of edges. Now,

note that each element ofwhich is not a corner of must lie

on eitheror tiles -- hence it has even degree in . But since the origin lies on only one element of

, there must be

another point oflying on an odd number of tiles. Thus, there

must be another corner ofthat lies in . Therefore, either

the width or the height ofis an integer.

Figure 3. A portion of the bipartite graph formed by a special tiling of a rectangle.

From the point of view of a particular practitioner, these two proofs

might present very different sets of epistemic benefits and drawbacks.

To begin with, for a student with no knowledge of basic graph theory,

the checkerboard proof is obviously more comprehensible. Therefore, with

Burgess' conception of rigor in mind, it makes sense to evaluate these

cognitive benefits in terms of a practitioner with sufficient background

in relevant areas of mathematics. Even then, a mathematician with

sufficient background for both proofs might feel a particular affinity,

hence be more likely to recall (an epistemic benefit), for one or the

other proof. For example, a graph theorist might be more drawn to the

bipartite graph proof; similarly, a mathematician with a preference for

constructive proof might prefer the bipartite graph proof.

Indeed, these proofs were posited by different mathematicians as being

the most proofs of the fact, even though they are so different with

respect to the techniques used; thus it is reasonable to assert that, to

the mathematician that formulated each proof, his own proof provided the

greatest epistemic benefit. Indeed, this is an ipso facto description

of mathematical practice: a mathematician proves propositions in the way

that makes the most sense to him. This principle contributes to an

account for the common mathematical practice of publishing new proofs of

previously established results. The rectangle-tiling theorem is a

particularly concrete example of this phenomenon, but this practice in

general speaks to the legitimacy of epistemic benefit (as well as

mathematical purity) as a quality that is valued by mathematicians, even

though it has no bearing on formal soundness.

To isolate what is happening here, it is helpful to actually name some

potential epistemic benefits and drawbacks of mathematical proof, and to

analyze them in the case of the two proofs of the rectangle tiling

theorem. De Toffoli mentions cognitive efficiency as a major epistemic

boon that is often bolstered by the inclusion of diagrams. Another

benefit is the ease with which a practitioner can verify the claims made

by the author of a proof. In this respect, the proofs of Theorem 1 have

a similar structure: after relevant definitions and setup are given,

each proof has one central inferential step which constitutes the crux

of the argument. In the former, it is the verification that

not contain an equal amount of black and white; in the latter, it is the

verification that each of the interior points of

in which one actually performs these verifications is also quite

similar. In each case, these claims are quickly checked by means of a

visualization of a general version of

on paper. Suggestive heuristic diagrams were provided in the original

versions of both proofs. In this sense, these proofs are similar with

respect to the epistemic benefit of ease of verification.

Another epistemic benefit might be the ease with which one can

communicate a proof in an informal setting -- this also contributes to

the ease with which a mathematician is able to recall and recreate a

proof. Once again, these two proofs of the tiling theorem are quite

similar in this respect. In presenting the checkerboard proof, one might

draw (on a chalkboard, for example) a sketch of a tiled rectangle, along

with a few suggestive squares of a checkerboard lattice. For the

bipartite graph proof, the same sketch might be drawn, supplemented

instead by a few edges of the bipartite graph, making sure to include

the odd degree vertex at the origin. This also sheds light on a

potential epistemic drawback shared by these two proofs: a dependence on

a certain level of spatial intuition from the reader.

This analysis makes clear two things:

an explicit characterization of what is meant by an epistemic benefit or

drawback. Here, we must tread carefully: if we are to redouble De

Toffoli's defense of the context of epistemic benefits and drawbacks

against Burgess' skepticism regarding heuristic or illustrative

diagrams, it is desirable that this conception of proof identity does

not distinguish along axes of explanatory power, methodological purity,

mathematical beauty, or other features of proof presentations relating

to mathematical aesthetics. If two proofs of

explanatory power are individuated in this context, De Toffoli's

argument meets a roadblock: then, a merely heuristic diagram (rather

than a diagram comprising honest-to-goodness mathematical notation)

could be considered essential to the identity of a proof.

And,

sufficiently generic mathematical practitioner; the cognitive benefit

offered by a proof might vary significantly depending on the background

and strengths of the reader.

In general, we may characterize an epistemic benefit as a feature of a

proof presentation that contributes to a generic practitioner's accurate

discovery, understanding, or communication of the proof. Similarly, an

epistemic drawback is a feature that detracts from a generic

practitioner's accurate discovery, understanding, or communication of

the proof. Here, is in reference to consistency with the established and

accepted body of mathematical knowledge. A generic practitioner is a

typical working mathematician with sufficient background to understand

and engage with the proof presentation in question.

Purity and Epistemic Benefit

De Toffoli describes the context of mathematical purity for

individuating proofs. Roughly, two proofs may be identified in this

setting if they use the same central idea. Furthermore, a proof of

whether it uses only the language, methods, and assumptions of that

which lies in the presentation of the proposition[10]. But, in fact,

this feature of a proof can grant significant epistemic benefit.

Consider, for example, the development of the modern field of

Hodge theory. Inspired by the famous comparison theorem of de Rham,

which establishes an isomorphism between the de Rham cohomology and the

Betti cohomology of complex algebraic varieties, a deep and far-reaching

link between geometry and topology. The classical proof of this result

centers around an application of the Poincaré lemma, a statement about

the same differential forms used to define de Rham cohomology in the

first place.[11]

This field was revived in the 1970s, when, spurred by developments in

algebraic geometry and Alexander Grothendieck's introduction of étale

cohomology, mathematicians sought to devise an analog of the de Rham

theorem for the étale cohomology of schemes over the

In 1988, Gerd Faltings proved Jean-Marc Fontaine's 1981 conjecture of

the existence of such an analogous isomorphism, but the structure of

Faltings' proof bore almost no resemblance to the classical

picture.[12]

This field was revived in the 2010s when Alexander Beilinson, in order

to formulate a proof of Fontaine's conjecture using geometric

techniques, formulated a

enabled a proof of the existence of the

with the same overall structure as the classical proof. Beilinson's work

was remarkable for several reasons. To begin with, it presented

significant practical advantages for practitioners to understand and

communicate the proof; it is much easier to grasp the overall structure

of Beilinson's proof than Faltings', as the reader is able to compare it

at each step with the well-established classical proof of de Rham's

theorem. Indeed, the overarching structure of Beilinson's proof is

remarkably similar to the picture for complex varieties, as shown in. In each case,

the desired map

enabled in each case by an application of the appropriate version of the

Poincaré lemma -- note the similarity of the corresponding commutative

diagrams. Though Beilinson's proof is not necessarily simpler or more

accessible than Faltings' in its own right, it succeeds in placing the

large-scale structure of the proof in a well-known existing mathematical

framework.[13] This benefit demonstrates the epistemic power of

methodological purity and aesthetic alignment.

Beilinson's proof led to an era of fruitful mathematical discovery, on

the back of this new perspective in

mathematical discovery using Beilinson's technique. Within the space of

a few years after the publication of Beilinson's proof, more progress

was made in the field than in the decade prior. Most notably, Bhargav

Bhatt enjoyed great success extending the

much more general settings, and furthermore he adapted other classical

results in Hodge theory to the

framework, most notably the theory of spectral sequences.[14]

Note that Beilinson's proof should be distinguished from Faltings' in

other respects as well. In the context of strength and generalizability,

for example, it is much more far-reaching; in the context of purity, it

is much more methodologically pure.[15] The techniques used, the

definitions made, and the theory developed differ significantly for the

two proofs. Even still, they are also individuated purely on the basis

of epistemic benefit; this emphasizes the interplay between

distinguishing proofs in different contexts of investigation. There is a

case to be made that mathematical purity in most cases contributes

positively to epistemic benefit. De Toffoli hints at this in the case of

using polygon diagrams to prove statements about surfaces, mentioning

that It is thus reasonable to assert that using relevant diagrams as

such, in contributing to methodological purity, both contribute to

accurate understanding of a proof and to providing intuition about the

proof technique that can stimulate the discovery of related

propositions.

Here we must be careful. As mentioned before, it is not desirable for

the criterion of proof identity induced by epistemic benefits and

drawbacks to be so coarse as to allow merely heuristic mathematical

diagrams to distinguish proof presentations from their non-diagrammatic

counterparts. However, diagrams are a special case -- in the purview of

acceptability in mathematical practice,[16] it is paramount that

diagrams meet some concrete standards for acceptability and mathematical

rigor, like those laid out by De Toffoli. On the other hand, for a proof

that does not contain notational diagrams as an essential component,

explanatory arguments, can in many cases (as in the Beilinson example)

contribute to accurate discovery, understanding, and communication in

their own right. In either case we are requiring that the epistemic

benefits are supported in a rigorous and mathematically acceptable way.

This discussion sheds light on the composite nature of proof identity,

and consequently the difficulty of formulating a satisfactory set of

criteria for individuating proofs. Though De Toffoli gave examples of

differentiating proofs based on epistemic benefit in the cases of proofs

containing notational diagrams, the aim of this section was to

understand how we might differentiate proofs along these lines in a more

general setting, in order to suggest that this way of individuating

proofs is well-behaved on a larger set of proof presentations.

Conclusion

Following De Toffoli's work justifying the essential role that certain

diagrams can play in the identity of mathematical proofs, we have

clarified the definition of epistemic benefits and drawbacks and

addressed the nature of the generic mathematical practitioner on which

this system relies. In short, an epistemic benefit (resp. drawback) is a

feature of a proof presentation that enhances (resp. hinders) the

discovery, understanding, and communication of the proof by a generic

practitioner. Epistemic benefits manifest, among other ways, as features

that reduce the cognitive load required to grasp, verify, or generalize

a proof. Some ways that they are realized in practice might be by use of

notational diagrams, as explored by De Toffoli, explanatory power,

methodological purity, or by placing an argument in an existing

mathematical framework.

The examples of the rectangle-tiling theorem and Beilinson's proof of

the comparison isomorphism demonstrate that we can distinguish along

lines of epistemic benefit in settings beyond proofs that contain

notational diagrams versus those that do not. This suggests that this is

a reasonable way to distinguish proofs in general, and indeed provides a

more general structure in which De Toffoli's contentions might fit. We

also addressed skepticism that might arise from the agent-dependence of

this practice. We also discussed why one must be careful when evaluating

epistemic benefits in the case of notational diagrams, as opposed to

usage of non-notational diagrams in proofs, in order to maintain

mathematical rigor and acceptability.

Additionally, we discussed the interplay between methodological purity,

rigor, and epistemic benefit, as well as the relationship of these

qualities with mathematical aesthetics. This is an area that merits more

exploration in future work.

De Toffoli (2023) ↩︎

Burgess(2015) ↩︎

See Manders (2008) for discussion of exact and co-exact features

of mathematical diagrams. ↩︎in the sense of De Toffoli (2020) and the discussion of rigor and

intuition in topological arguments. ↩︎See De Toffoli (2020) for discussion of criteria of acceptability

in mathematical practice ↩︎See Gowers (2024) ↩︎

De Toffoli (2023) ↩︎

Wagon (1987) ↩︎

This is a special case of a theorem of De Bruijn concerning

packing-dimensional bricks in an -dimensional box. See De

Bruijn (1969) for more details. ↩︎Mancosu and Arana (2005) ↩︎

See, for example, Voisin and Shneps (2003) for more details. ↩︎

see Fontaine and Messings (1987) and Faltings (1988) ↩︎

See Beilinson's paper Beilinson (2011) for the original proof.

Szamuely and Zabradi (2018) is a much more accessible version of

Beilinson's argument, with helpful context and background. ↩︎See Bhatt (2012) ↩︎

Luc Illusie compares the structure of Beilinson's proof in

Illusie (2013) ↩︎Acceptability in the sense of De Toffoli (2021), as distinct from

mathematical rigor ↩︎